February 20th, 2023

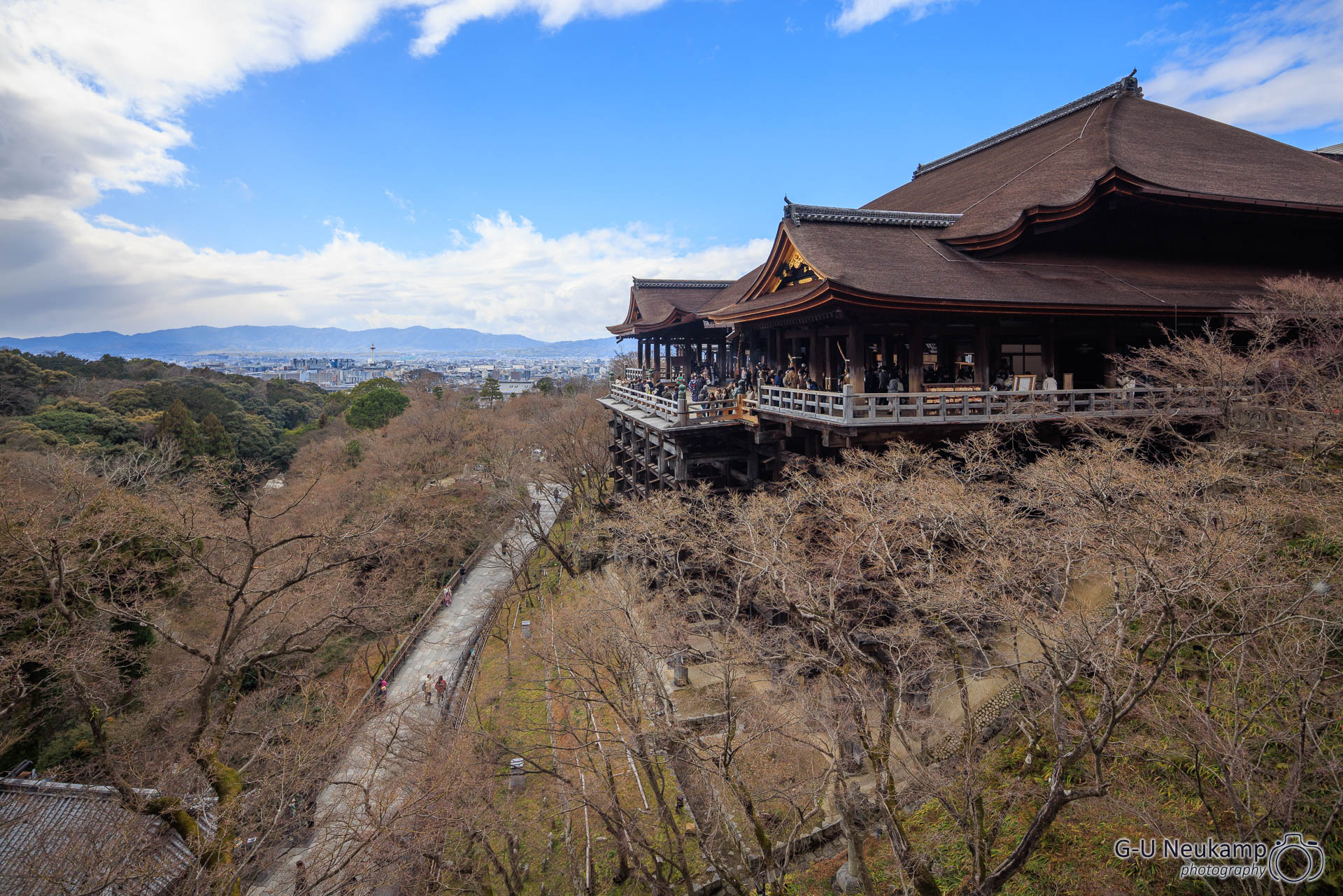

On our first morning in Kyōto, we took a bus to the Kiyomizu-dera temple. The Otowasan Kiyomizudera (音羽山清水寺) in the Higashiyama district is one of the city’s most famous sights. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site Historic Kyōto (Kyōto, Uji and Ōtsu) in 1994 along with other sites. The Kiyomizu-dera is the sixteenth temple of the Saigoku Pilgrimage Route (西国三十三箇所, Saigoku sanjūsankasho).

The history of the temple dates back to 798. However, the current buildings were erected in 1633. It got its name from the waterfall inside the temple complex that comes down from the nearby hills - kiyoi mizu (清い水) literally means “pure water”. On the main access road to the temple, many souvenir stores line up. On the street you can see many people dressed in traditional kimonos, mostly young women.

The main hall of Kiyomizu-dera is known for its wide terrace, built together with the main hall on a framework of wooden beams on a steep hillside. Its terrace offers an impressive view of the city. The temple has bought up the surrounding land, preventing the construction of high-rise buildings.

Trivia: The Japanese phrase “jumping down the terrace of Kiyomizu” (清水の舞台から飛び降りる kiyomizu no butai kara tobioriru) means “to make up one’s mind”. This is reminiscent of a tradition from the Edo period, according to which a person who dared to jump down from the terrace would have all his wishes granted. This seems believable because the lush vegetation below the terrace cushions the impact. 234 jumps were documented in the Edo period and of those, 85.4% of the jumpers survived the jump (nowadays, however, it is illegal to jump from the terrace). The distance from the terrace to the bottom is only 13 m, but this is an impressive height for such a wooden structure.

The temple was very busy, in general there was a lot going on in Kyōto. Somewhat apart from the main temple was a small pagoda and it was a little calmer there.

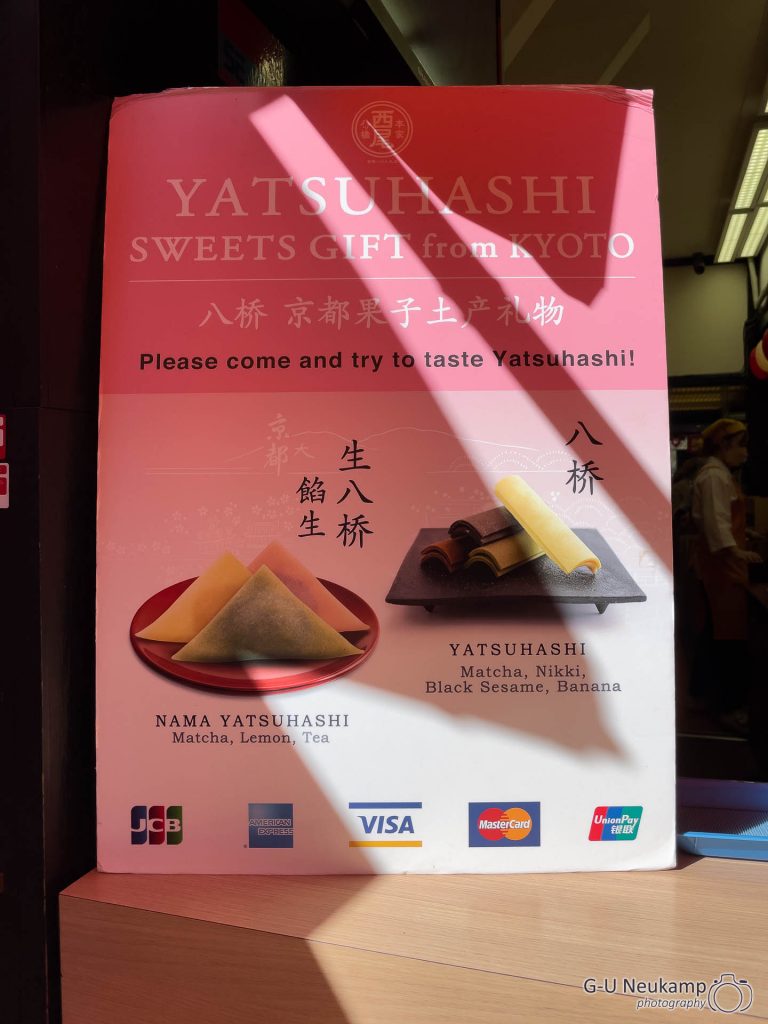

On the way back, we found several stands selling yatsuhashi (jap. 八ツ橋), a candy very popular in Kyōto. In one store, you could try them. They were very tasty and we got plenty of them.

After visiting the temple complex, we walked back down through the narrow streets and even found a Starbucks. However, this time it was completely in the style of a teahouse.

From the café we walked down to Yasaka Pagoda. The street overlooking the pagoda is probably one of the most famous photo spots in Kyōto. Many young people in gorgeous kimonos strolled down here. In beautiful light, this resulted in wonderful motifs. Here is one of my favorite pictures of this trip:

We then continued towards Heian-jingu shrine and found a few more shrines and temples, but this is not difficult in Kyōto. There is something to see everywhere. Here are some pictures of the Yasaka Shrine. Simone and Luise got another stamp for their Goshuincho books.

The Japanese Goshuincho is a book that can be presented at temples and shrines in Japan to receive a stamp as a souvenir.

Literally translated, the name means “venerable red stamp book” and owning one makes any traveler more than a mere tourist. Japanese often own such a stamp book and take it with them when traveling in Japan to get a personalized souvenir at various temples and shrines.

After that we went to the Chion-in temple. After the entrance you first have to climb a very steep stone staircase - no wonder, the name of the temple means something like “mountain peak”.

Finally, we reached the last temple / shrine of the day and thus the number four, the Heian Jingu. We had definitely already visited it in 2014. The large complex is very impressive with the wide area and the huge torii at the entrance and the colors are also always great.

On the way back we discovered the Buddhist Myoden-ji temple with the statue of the monk Nichii, who founded it. Unfortunately, it was already closed, so Simone and Luise could not get another stamp for their book.

For dinner, Luise had reserved a table at “Daishogun,” a restaurant that offers yakiniku. Meat and vegetables are roasted on a gas grill embedded in the table. In addition, one can order all kinds of side dishes. Again, this was done by scanning a QR code on our cell phone. We had Caesars salad, kimchi and fries. We also had shrimps - which required manual work. In Japan, you usually eat shrimps in their shells, but we didn’t go that far.

It was incredibly good, of course we took the most expensive range of meat, with Wagyu beef. Luise ordered a soju to try this once. However, there then came a 360 ml bottle with 13% alcohol - it turned out to be a very funny evening. For dessert we had a matcha ice cream crème brûlée - delicious.

Trivia: Yakiniku (jap. 焼(き)肉, engl. “grilled meat”) refers to the technique of preparing meat on a grill in the Japanese style. This is relatively new in Japan. Japan has a long history of recurring official bans on meat consumption. It was not until the Meiji Restoration in 1871, with the intention of becoming more western-like, that the ban was finally lifted for all levels of society and meat became widely available in the Japanese diet. Tenno (Emperor) Meiji personally spurred the campaign for meat consumption by publicly eating beef on January 24, 1873. The terminology originated from this time.

In 1872, in the then famous cookbook Seiyō Ryōritsu (西洋料理通, roughly: “Manual of Western Cuisine”) by Kanagaki Robun, as well as in the Seiyō Ryōri Shinan (西洋料理指南, roughly: “Introduction to Western Cuisine”) book by Keigakudō Shujin, the terms for grilled meat and steak are translated as yakiniku (焼肉) and iriniku (焙肉).